2009 Union Hall of Honor

Webtrax Admin

James. C. Petrillo

Into the conplex and turbulent organizational stew of early musicians’ organizations and their relationship to the burgeoning labor movement stepped James C. Petrillo, a young son of the rough and tough Chicago West Side. Petrillo had taken trumpet lessons at Hull House and headed a dance band which had joined a musicians group closely associated with the Chicago Federation of Labor. In 1914 at age 22 he was elected Vice President. Defeated in 1917, he switched over to Local 10 of the American Federation of Musicians (AFM) where he was assigned the job of organizing musicians in the Chinese restaurants. With that mission accomplished, in 1919 he was elected Vice President of Local 10. Following a lengthy period of internal conflicts within Local 10, Petrillo was elected President in 1922. Foresaking his trumpet, Petrillo turned all his energies to solving the issues confronting Local 10. The first issue was a demand on radio stations to pay wages to musicians who were performing on the air. The stations claimed that the musicians were receiving free publicity, and hence did not deserve cash pay as well. Ultimately, the radio stations bowed to the union’s pressure. Soon after, in 1924, the front porch of Petrillo’s home was wrecked and the windows blown out by a bomb.

In 1927, the Chicago local went on strike against the moving picture palaces. An injunction was sought against Petrillo in Federal Court but it was blocked by union lawyers, among them Clarence Darrow. After four days the union’s demands were accepted. In 1931, the threat of a strike brought an agreement between Local 10 and Chicago’s major hotels. The union then went on to win wage increases at restaurants, theaters, the Opera and the Symphony. With Local 10’s success at the bargaining table, rival groups began affiliating, including the union group which Petrillo had joined as a youngster.

With the coming of the Great Depression, overall employment of musicians fell drastically. In order to deal with unemployment, Petrillo conceived the idea of free concerts in public parks, but the City was not interested in such “extravagances.” Petrillo continued to press the political front by securing an appointment to the West Park Board and then through Mayor Kelly an appointment to the Chicago Park District Board. In 1935, this Board did respond favorably to Petrillo’s idea of concerts in the park, but declined to finance the project. So Local 10 appropriated many thousands of dollars from its own treasury to launch the free Grant Park summer concerts. The phenomenal public attendance convinced the Park Board to underwrite future concerts. Even so, the union had to pay for any soloists.

Still concerned about unemployment among musicians as a result of “canned” music on the radio, Local 10 announced that union members would not be permitted to make recordings as of February 1, 1937. Although this action might result in a shift of recording work to other cities, Petrillo argued that someone had to start the ball rolling. At the national convention that year under President Weber, it was agreed to call on industry to negotiate the issue of canned music. After fourteen weeks of intense negotiations a two-year agreement was reached under which radio stations would increase employment of staff musicians in exchange for continued use of recorded music. Also, the recording industry agreed to use only union musicians. Weber retired at the 1940 convention after 40 years as president. Petrillo was elected unanimously to suceed him. His hand thus strengthened, Petrillo repened his campaign against canned music. In June 1942 the union announced that after August 1, AFM members would no longer make recordings. This action was supported by the AFL convention in October.

The ban on recordings ran into intense political opposition in the name of supporting the war effort. In February 1943 the union proposed that companies pay small fees for each record produced. These fees would be put into a fund to reduce unemployment among musicians. The companies refused. Finally in November 1944, Columbia and RCA yielded and agreed to a three-year contract that accepted the recording fee concept. This settlement laid the basis for the Music Performance Fund of today, an independent non-profit organization which administers funds to support free public concerts. Unfortunately, due to changes in the recording industry, this fund is no longer receiving adequate contributions from the industry.

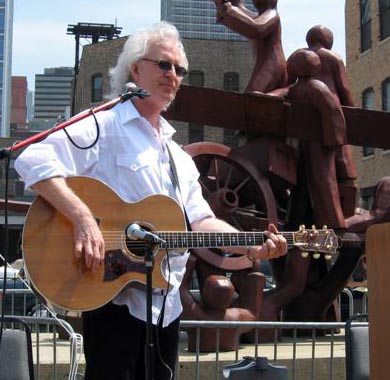

Bucky Halker

Bucky Halker was born in Beaver Dam, Wisconsin, in 1954 and raised in Ashland, Wisconsin, a declining blue-collar, iron ore, and lumbering town on the shores of Lake Superior where fishing, hunting, taverns, polka bands, and fish fries held sway. The region was home to second-generation Swedes, Finns, Norwegians, Serbs, Poles, Croatians, Anglos and a large Indian population. Like fellow “jackpine savage” Bob Dylan, Bucky learned the meaning of class, race, and ethnicity in this environment. However, he credits his grandfather, a Chicagoan and long-time stockyard worker, and his aunt, a Chicago teacher and life-long union activist, for his strong sense of labor history, democratic reform, and history “from the bottom up.”

At the same time, he blames his mother and girls for leading him down the wayward path of a musician and his father for his deep distrust of centralized authority. Bucky did pursue an interest in labor and history as far as a PhD (University of Minnesota). He also has a long record of scholarship, including reviews, essays, fellowships, awards, and guest lectures in the US, Canada, and Europe. He is the author For Democracy, Workers, and God: Labor Song-Poems and Labor Protest, 1865-1895 (University of Illinois Press, 1991) and “Local 208 and the Struggle for Racial Equality” (BMR Journal, 1988). Nevertheless, Bucky left his tenure-track job more than twenty years ago in an effort to take both labor songs and his own music into a larger public arena.

At 13, Bucky began writing songs, playing the guitar, learning folksongs, and performing with his own rock band. He tours extensively in the US and Europe and has released seven original-song recordings, most recently Wisconsin 2-13-63, Vols. 1 & 2. He has also recorded renditions of labor protest songs, including Welcome to Labor Land, a collection of Illinois labor songs recorded for the Illinois AFL-CIO. To date, he has presented more than 300 concerts of labor protest and Woody Guthrie songs. He also produced the critically acclaimed three-CD series, Folksongs of Illinois (University of Illinois Press). He is a member of American Federation of Musicians Local 1000 and serves on the board of directors for the Woody Guthrie Foundation and Archives in New York City (www.woodyguthrie.org).

Local 208 Chicago Federation of Musicians

When the American Federation of Musicians was founded in 1896 and Chicago’s Local 10 in 1901, thousands of African-American musicians sought membership in the union. Excluded by the national and local union because of their race, however, Chicago’s African-American musicians formed Local 208 in 1902. Under those segregated condition, Local 208 nevertheless grew and established itself as a powerful and influential voice in the music community. By the end of WWI the local owned a three-story office and practice building on south State Street. Years later it was also own an apartment building in Hyde Park, which offered reduced rent for professional musicians. The local was also able to enforce a wage scale among theaters, social clubs, organizations, and larger clubs where musicians performed. The leadership also enjoyed cordial relations with the white Local 10, even as it continued to press for equal membership throughout the 1930s and 40s, particularly after the rise of the C.I.O. and its integrated unions.

The list of Local 208’s membership over the years is a testimony to the talented musicians in its ranks. The list reads like a Who’s Who of Chicago music and included Louis Armstrong, Bo Diddley, Nat King Cole, Willie Dixon, Muddy Waters, Ahmad Jamal, Lil Armstrong, Howlin’ Wolf, Reverend Thomas Dorsey, Cab Calloway, Milt Buckner, Buddy Guy, King Oliver, Erskine Tate, Eddie South, Red Saunders, and many more.As the Civil Right Movement gained momentum and African-American music began their own national movement to integrate the AFM, pressure increased end segregation in the Chicago ranks as well. Finally, in January of 1966 Local 10 and 208 were merged and equality finally came to the Chicago AFM.